Leadership Voice:

Hui Wu-Curtis

President & COO, World Connection

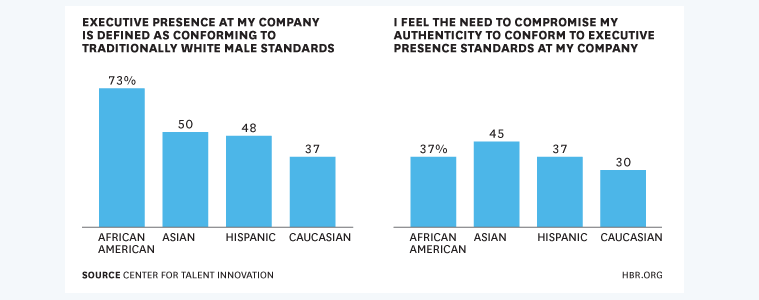

In a previous position, one of my supervisors had told me that her manager recommended she find one or two mentors as part of her professional development. He was trying to help her work on her executive presence. He’d recommended a few choices but the supervisor, being of Hispanic dissent, said she preferred more diverse mentors. She wanted to work with and get perspective from other minorities leaders within the company. The manager, being a minority male himself, asked, “Why would you want to do that?” In that work environment, executive presence was defined by conforming to norms set by conservative, white men. In part, to move up the corporate ladder, one had to lose a bit of their own identity to behave and act in a certain manner. One was encouraged to network and create more advocacy and relationships with others to help your career. Coincidentally, the network of leadership was predominantely Caucasian.

In a Harvard Business Review article, “Cracking the Code that Stalls People of Color,” executive presence rests on three pillars: gravitas, an amalgam of behaviors that convey confidence, inspire trust, and bolster credibility (and the core characteristic, according to 67% of the 268 senior executives surveyed); communication skills (according to 28%); and appearance, the filter through which communication skills and gravitas become more apparent (5%). While they are aware of the importance of executive presence, men and women of color are nonetheless hard-pressed to interpret and embody aspects of a code written by and for white men.

Much of the existing literature about executive presence is earmarked for individuals that are mid to higher level leaders looking to get to that executive-level position; however, many of the same concepts can apply through our coaching and development, even at a supervisor level.

As I sat in a meeting with one of our vendors, we had a good cross-section of representation of my leadership team, from supervisors to directors. As our vendor was soliciting feedback from our team, one of my supervisors, of Hispanic dissent, was really stumbling over his words. His comments and thoughts were fragmented, and he seemed nervous. Normally, this supervisor is outgoing and not afraid to speak his mind. I sat and observed the dynamics of the room. I realized this supervisor was trying to sound more professional in that meeting by using larger vocabulary words. He was trying to fit in with the audience of other leaders — predominantly white females — and present himself in a way that was not him. So rather than focusing on providing constructive feedback and creating good dialogue, he was more concerned with acting and appearing a certain way. The supervisor was trying to act more like the understood norm of the company’s cultural definition of executive presence — more sophisticated, more white.

I provided this observation to this supervisor’s manager, explaining that a person can be themselves culturally — be more authentic. I place more value on ideas and the content within the dialogue versus how people say things or how people appear compared to others. So I advised that, next time, this supervisor relax and focus on being himself and, in the next meeting, he did a great job contributing to the conversation. People were impressed by his observations. He was more relaxed, allowed himself to be more natural in his Hispanic nuances, and felt safe and confident that he also deserves to be at that table with everyone else.

As leaders, we hear the term inclusion and diversity in many organizations, but how does one really coach and mentor towards these ideals? I may be a bit more sensitive, being a female, minority Asian leader in predominately male or white male industries. There were very few minority role models or mentors as I was moving up the corporate ladder to help me understand executive presence through a minority lens. Our journey towards defining executive presence as minorities is different, whether we like to acknowledge that fact or not. Minorities go through a different set of challenges, unconscious biases, and internal struggles thinking that one has to give up their cultural identity to ‘fit in’ and be more white in corporate America. Different does not mean bad or wrong — it is just different.

As leaders, regardless of race, we must first create a safe environment for people to be genuine, accept and value diversity, and embrace people’s uniquely different styles, approaches, and points of view. A leader must be aware of their own unconscious bias and discourage judgement from others because someone is different. And as leaders, don’t be dismissive of other people’s unique challenges as minorities in the workplace — especially ones looking to progress in their career.